You know you are on to something special when researchers who have traveled to and experienced the wonder of some of the most remote places on Earth are captivated by a tool that takes them there virtually.

Earth’s cryosphere, including its ice sheets, ice caps, glaciers, and sea ice, is undergoing stark changes as air temperatures continue to rise. Scientists who study these regions understand viscerally the scale and scope of these changes, but they encounter limitations in communicating their experiences and observations to the public. Digital learning tools and online scientific data repositories have greatly expanded over the past decade, but there are still few ways for the public to explore rapidly changing icy environments through a realistic platform that provides contextual information, supplemental media, and connections to data sets.

Create Your Own Virtual Field Experience

- Byrd Center’s instructional guide

- Record: GoPro MAX 360° waterproof VR camera

- Edit footage: Adobe Premiere Pro

- Add location data: Dashware

- Host videos to access in tour: Vimeo

- Add 3D objects: Sketchfab

- Add the virtual tour overlay: 3DVista

The Virtual Ice Explorer (VIE) aims to bring the public closer to these important places. Developed by the Education and Outreach (E&O) team at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, VIE encourages informal learning about icy environments by immersing visitors in “choose your own adventure” tours. Click on the globe on the home page and head to, for example, the Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC) expedition that intentionally froze its ship into Arctic sea ice for a year of observations last year. You’ll land on the deck of the icebreaker R/V Polarstern overlooking the ice camp—no long voyage required. Next, you can visit scientists in action, sampling Arctic waters up to 1,000 meters below the ocean surface through a hole drilled in the ice. Or maybe you’d like to see how researchers spend their off hours with a little snow soccer. These options offer visitors a glimpse into the daily lives of scientists in the field as they fill in the blanks about what researchers study in these extraordinary locations and why it matters to our understanding of the planet.

DIY-ing the First VIE

VIE was originally conceived as a platform to display immersive tours for about a dozen glacial sites around the world, generated from digital elevation models draped with satellite imagery. Following setbacks caused by the quality of the virtual landscapes created from satellite data and challenging user experience, two opportunities allowed us to reenvision VIE: (1) the acquisition of rugged, easy-to-use field cameras and (2) our discovery of existing commercial software with which we could more easily create tours that had been painstakingly built with custom code. We also began involving researchers who visited these sites firsthand; their experiences turned out to be essential for our tour development.

Our team purchased a GoPro Fusion 360° camera by way of a generous donation to the Byrd Center. At the same time, Michael Loso, a geologist with the U.S. National Park Service, was planning to spend a field season at Kennicott Glacier in Alaska. Loso agreed to take the camera and capture footage. We shared his footage using a virtual reality (VR) headset during Byrd Center outreach events and with park visitors, and also collected feedback. We were particularly moved by a visitor who appreciated that the tour allowed them to explore a site that was otherwise inaccessible due to a physical disability.

This ease of use in the field was an essential criterion if we were to ask scientists to carry the cameras along on expeditions.

These rugged, inexpensive, and relatively easy-to-use cameras come with their own software and have a multitude of third-party programs available. Researchers can set them up, hit record, and walk away to focus on their work. This ease of use in the field was an essential criterion if we were to ask scientists to carry the cameras along on expeditions. After capturing and rendering video using GoPro’s software, we use tools like Adobe Premiere Pro for additional editing, Dashware for accessing location data, and Plotly’s Chart Studio for graphing and hosting interactive data sets.

A workshop run by Ryan Hollister, a high school educator, during the 2019 Earth Educators’ Rendezvous also led to tremendous advances in our team’s ability to create VIE tours. Hollister showed off the immersive virtual field experience he created for the Columns of the Giants in California and walked attendees through designing their own experiences. After collecting 24 panoramic images with a Nikon D750 camera, Hollister stitched them together to create a 360° image using Autopano Giga software. He then used 3DVista software to add an interactive overlay to the images that allowed users to move to different locations within a site, click on marked points of interest and read about them, and embed 3D models of rock samples. This software was originally designed for architects and real estate professionals to create virtual tours of buildings, so it seamlessly constructs the computer code underpinning the tours with landscapes. Today 3DVista caters to wider audiences, including educators, and it provides services such as live guided tours and hosting capabilities.

The 3DVista software allowed us to create glacial landscape tours that we had been building with customized computer code, but in far less time. Use of off-the-shelf software allowed us to spend more time collecting footage, creating compelling narratives, and testing a wider range of scene designs. In the future, we plan to use 3DVista’s user-tested interface to train educators and researchers to create their own tours.

Getting Scientists Camera-Ready

The E&O team now trains Byrd Center researchers with the cameras on basic photography techniques and more specific 360° filming techniques to capture high-quality video for VIE and other outreach programs. We want researchers to illustrate the vast, unique landscapes in which they’re working as well as showcase engaging scenes from their day-to-day experiences. We train them to create compositions to fill a scene, such as the inclusion of people to provide scale and demonstrate the research process, and we encourage them to film all parts of the expedition, including the journey, their living conditions, and interactions with collaborators and local partners.

We also have conversations with expedition members on the nature of their research, the field site itself, the equipment that will be on-site, and the desired impact of our outreach so that we can coproduce a narrative that guides what they film. These training sessions help the E&O team consider unique content for each tour, such as maps of study sites, time-lapse series, information on samples and equipment, biographies of researchers, links to publications, and prominent messages that properly identify and give respect to the people and places shown.

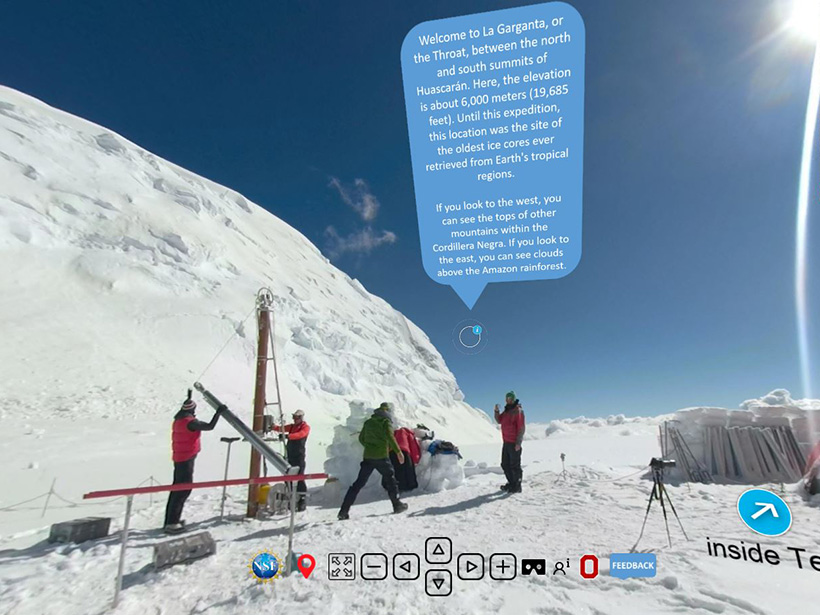

A benefit of having researchers explore virtual tours of other sites before they embark on their journey is that it generates genuine enthusiasm to share their own experiences. Chris Gardner, a Byrd Center researcher, viewed a tour of ice core drilling on Mount Huascarán in Peru while preparing to lead an expedition to the Dry Valleys of Antarctica during the 2019–2020 field season. Once he could see what was possible, he met with the E&O team to develop a video capture plan. Importantly, Gardner involved his entire team in selecting shots, recording video, and contributing to the tour narrative.

Authors Kira Harris and Kasey Krok have participated in many of these training sessions as undergraduate interns on the E&O team. They found that these sessions offered opportunities for pivotal interpersonal interactions among group members, including undergraduate and graduate students, postdocs, and investigators. Students gained a better understanding of the science that researchers were carrying out, while getting an opportunity to share their sometimes more finely honed technical experience in video and photography.

High-Quality Tours With a Low Lift

As of this writing, the Byrd Center has created virtual field experiences for eight sites, thanks to collaboration with the National Park Service, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, and the many scientists who filmed their field campaigns. Additional examples of virtual field experiences by other groups include VR Glaciers and Glaciated Landscapes by Des McDougall at the University of Worcester; The Hidden Worlds of the National Parks by the National Park Service; and these immersive virtual field trips by Arizona State University. More are being developed all the time. At AGU’s Fall Meeting 2020, for example, there were numerous oral sessions and posters highlighting the applications of virtual field experiences.

What’s most exciting is that these virtual explorations allow individuals almost anywhere in the world—regardless of their wealth, abilities, or learning preferences—to experience new landscapes and engage with Earth science lessons.

Our E&O team has published an instructional guide for educators and scientists to use to build their own virtual field experiences tailored to their initiatives, using the same workflow that we use. Ryan Hollister has several resources, including guides on the technical requirements for high-resolution tours, creating 3D models of rock samples, and how to use the Next Generation Science Standards to best adapt immersive virtual field experiences for all learners. Our team also continues to test new tour features that will increase user engagement, knowledge retention, and options for user interaction. Last year, while closed to the public due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we even created a virtual tour of the Byrd Center to continue reaching out to the thousands of individuals who typically visit our facility each year.

What’s most exciting is that these virtual explorations allow individuals almost anywhere in the world—regardless of their wealth, abilities, or learning preferences—to experience new landscapes and engage with Earth science lessons. While you can get the best view of the tours on a VR headset, all you need is a modest Internet connection and a laptop, tablet, or smartphone. These tours can be developed to specifically put visitors into the role of scientist to observe the terrain and use the provided data to make evidence-based claims.

This virtual field access enables individuals of all ages to get a taste of field research, appreciate the daily work of scientists, and gain a deeper understanding of our rapidly altering natural world. Although nothing can truly replicate an in-person field experience, virtual tours can be used to enhance educational opportunities in cases where people would otherwise not have access to those experiences, such as in large introductory courses, socially distanced laboratory exercises, or locations that need protection from oversampling or ecotourism. We can’t always bring people to the far reaches of the world, but we now have many tools to bring the vast world to each of us.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided by the National Science Foundation under award 1713537 and a contribution from ENGIE/Ohio State Energy Partners. We thank the MOSAiC expedition and the NSF Office of Polar Programs for their continued collaboration on this project.

Author Information

Kira Harris ([email protected]), University of Arizona, Tucson; Kasey Krok, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, Ohio State University, Columbus; Ryan Hollister, Turlock Unified School District, Turlock, Calif.; and Jason Cervenec, Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, Ohio State University, Columbus

Citation:

Harris, K., K. Krok, R. Hollister, and J. Cervenec (2021), Virtual tours through the ice using everyday tools, Eos, 102, https://doi.org/10.1029/2021EO160631. Published on 09 July 2021.

Text © 2021. The authors. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Except where otherwise noted, images are subject to copyright. Any reuse without express permission from the copyright owner is prohibited.